Key Signatures and the Ionian (Major) Scale

Things to read before Key Signatures and the Ionian (Major) Scale:

What are key signatures? Why are they there?

Tonality is the emphasis of one pitch over any other pitch being used. Think of it this way: if you can sing a pitch that seems like it is the most prevalent throughout a music work, then that music is tonal. Most of the music you have heard is probably like this. Almost all music before the 1850’s and all of popular music today is considered tonal.

Key Signatures and the Ionian (major) scale

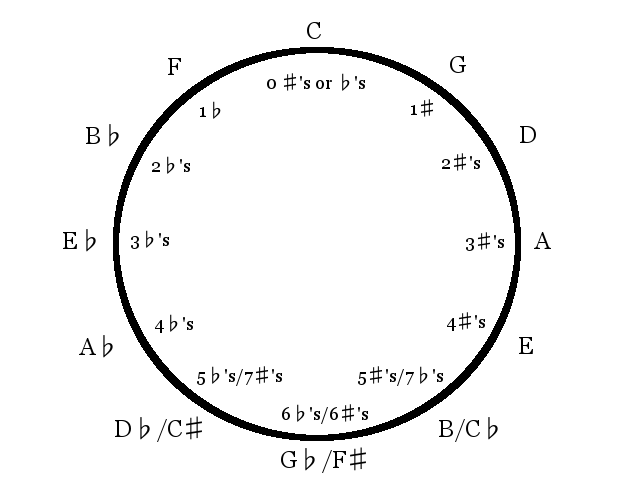

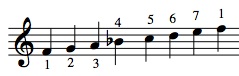

A scale is a pattern of pitches which occur in ascending and/or descending order. A scale degree is an individual pitch in a scale. The Ionian (or major) scale is the most common point of departure for learning tonal systems, so we will start there. It also happens to be the scale which is most common in western music and which seems to emphasize the pitch on which it begins and ends the most. To hear the scale, go to a piano and play a C. Then play every white key (in ascending order) one at a time until you reach the C above it (and then stop). C Scale You will notice that C is the pitch that is the most stable and most easily sung. When music is based upon this scale, the music is in the key of C Ionian. C is the pitch class being emphasized and the Ionian scale is being used to create this emphasis.

C Scale (Example 2-1)

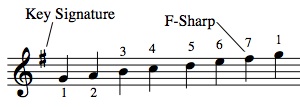

The Ionian scale can be used to emphasize any pitch class by starting the pattern on the pitch you wish to emphasize. This will put us outside the key signature of C. However, in order to maintain the same pattern of whole-steps and half-steps, accidentals must be used. In the C Ionian scale, there are two half-steps that conveniently fall on the half-step points occurring in the staff (one between E and F, the other between B and C). This pattern must be kept in order for the scale to be considered Ionian: there must be a half-step between the 3rd and 4th scale degrees as well as the 7th and 1st (note the numbers assigned to each note in example 2-1; these are the names for the scale degrees). For example, for the scale to still be Ionian and emphasize F, there must be a half-step between scale degrees 3 and 4; without any accidentals it is a whole-step. All that needs to be done is to lower scale degree 4 by a half-step, and the scale is Ionian once again. We do not raise the 3rd scale degree because that would cause the distance between 2 and 3 to be more than a whole-step. In other words, to make an Ionian scale that starts on F, we need to change the B to B-flat. We are now in the key signature of F.

F Scale (Example 2-2)

When in a key other than C, there will be certain notes that will always have the same accidental. For example, in the key of F Ionian the 4th scale degree will always be B-flat and not B-natural. Therefore, in order to simplify the appearance of notation, composers tend to use key signatures. A key signature is an accidental or a set of accidentals (without notes next to them) that tell the performer which pitch classes will always be altered. In example 2-3, we see that the key signature contains one sharp on the F line of the staff. This means that every F in this section of music should be changed to F-sharp. However, the key signature can be overruled by accidentals: a natural sign can be used to change the F-sharp back into an F-natural. (If you didn’t understand why naturals existed before, now you do.)

G Scale (Example 2-3

To go through the process of figuring out where to add which accidentals to what notes to create the Ionian scale for every pitch class would be a waste of time. There is a beautiful pattern that figures this out for us…