Don’t get excited. It’s a rare thing. Turning off the metronome is for professionals only. That is unless a professional told you to turn it off. If you’re a beginner musician, leave your metronome on. If you’ve been playing a while and can keep fairly steady time, this is where a metronome just might be holding you back from progressing.

Don’t get excited. It’s a rare thing. Turning off the metronome is for professionals only. That is unless a professional told you to turn it off. If you’re a beginner musician, leave your metronome on. If you’ve been playing a while and can keep fairly steady time, this is where a metronome just might be holding you back from progressing.

The traditional argument (and it’s a good one) is that if you can’t keep you part together with something predictable and solid, how are you possibly going to keep your part together with another person? That’s what Mommy told me in the 6th grade, and she was absolutely right. If you can’t keep it together with a metronome, you can’t keep it together with anything. But once a musician gets to a certain level of time keeping proficiency, there is a time to set it aside. There’s another aspect to metronome practice that can actually hold a musician back; aligning your body with itself.

The metronome is an external thing that each musician internalizes in order to all be on the same page. Each beat should be exactly as far away from the previous one so that everyone agrees on when to play the next note. But there are tiny details that have nothing to do with the metronome that get overlooked. Details that occur between each note outside of the pulse and they must occur in a certain sequence in order to be correct. For example, On a woodwind instrument, the throat position must change a split second before the fingers. Otherwise the next note will have a weak and anemic attack. A metronome might get in the way of learning this technique.

Turn Off the Metronome: An Example From Percussion

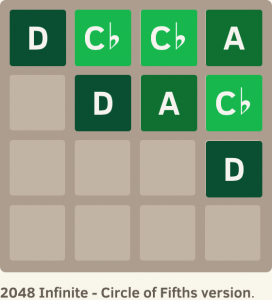

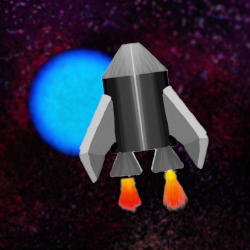

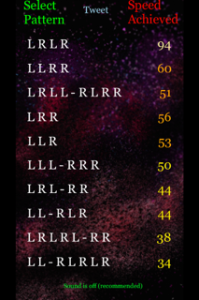

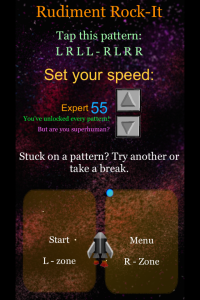

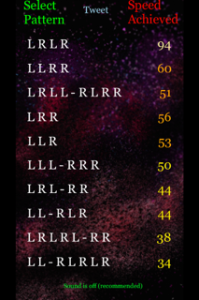

Rudiment Rock-It

Drum rudiments should almost always be practiced with a metronome. But there comes a time when a percussionists weaker hand becomes conditioned to be satisfied with not being as powerful. Their single stroke roll becomes permanently swung. Their double stroke roll is sloppy with a consistent decrescendo between the four taps. A metronome hides that defect from a student. Yes, leading left helps, but it doesn’t fix all of the problems. At some point, the parts of a person’s internal striking mechanism must be aligned to itself. A metronome will get in the way. Turn it off. Play the singly stroke roll slowly. Speed it up. Slow it down. Let yourself go into a sort of trance by focusing on the sound you’re making. Play at speeds you are comfortable with until you can’t figure out which hand is making which sound. Do the same with the other rudiments. You have already internalized the symmetrical proportion of time. You have mastered it. Trust your intuitive judgment, turn off the metronome, and efficiently make your weak hand stronger. Then turn it back on to see how much faster you’ve become in the past five minutes. It works, I promise.

Thanks to Rudiment Rock-It, beginners can now use this technique too. Teachers need not be worried about students developing bad habits. The game allows the player to speed up, but keeps track of the time passed between each tap. If the player becomes unbalanced in their timing, the rocket crashes and they lose. But before they crash, the game gives them a chance to slow down and regroup to try to win. So the gameplay encourages perfect and efficient practice without a metronome. There has never been a more fun or efficient way to learn the basic rudiments of percussion.

Thanks to Rudiment Rock-It, beginners can now use this technique too. Teachers need not be worried about students developing bad habits. The game allows the player to speed up, but keeps track of the time passed between each tap. If the player becomes unbalanced in their timing, the rocket crashes and they lose. But before they crash, the game gives them a chance to slow down and regroup to try to win. So the gameplay encourages perfect and efficient practice without a metronome. There has never been a more fun or efficient way to learn the basic rudiments of percussion.

This game is so efficient because it applies this theory of a metronome getting in the way of a musician’s body aligning with itself. Instead of an outside force beating a student into submission, the game tells the player what their striking mechanism is actually doing. A persons hands align themselves to each other without needing to think about the outside influence of a metronome, and one problem can be dealt with at a time.

Practicing with a metronome still solves the majority of timing problems. However, any problem that has to do with a person’s body sequencing events with itself might be better dealt with using alternate methods.

There will be more games like this. Stay “tuned.”

In honor of NaNoWriMo, I (Zach) wrote some python code to help you participate in this month of novel writing. The code below will read a text file online that contains a list of English words, then print out fifty-thousand of them for your brand new novel!

In honor of NaNoWriMo, I (Zach) wrote some python code to help you participate in this month of novel writing. The code below will read a text file online that contains a list of English words, then print out fifty-thousand of them for your brand new novel!

Don’t get excited. It’s a rare thing. Turning off the

Don’t get excited. It’s a rare thing. Turning off the

The

The